Following on from our Enzo Mari workshops in 2024 and 2025, Bob Richmond and Clarissa Berning are travelling to Japan in October 2025. The aim of the journey is to learn about Japanese methodologies and techniques, and to foster new dialogue around social design, in particular in relation to the democratising of making processes and their evenly-distributed outcomes. Enzo Mari had a long-standing collaboration with Muji, and we wish to continue this form of debate. The applicability of Mari’s Autoprogettazione in this context is freely open to question, and ultimately Mari’s design thinking has most potency when viewed as starting place, a release agent for creative agency.

The journey has been made possible with the generous support of The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation and The Guild of St George.

“Ultimately the goal of Enzo Mari’s Autoprogettazione is not to just offer measured drawings, rather it’s a manual to teach a vocabulary that anyone can use to design and build their own furniture.”

Enzo Mari’s furniture designs and Autoprogettazione

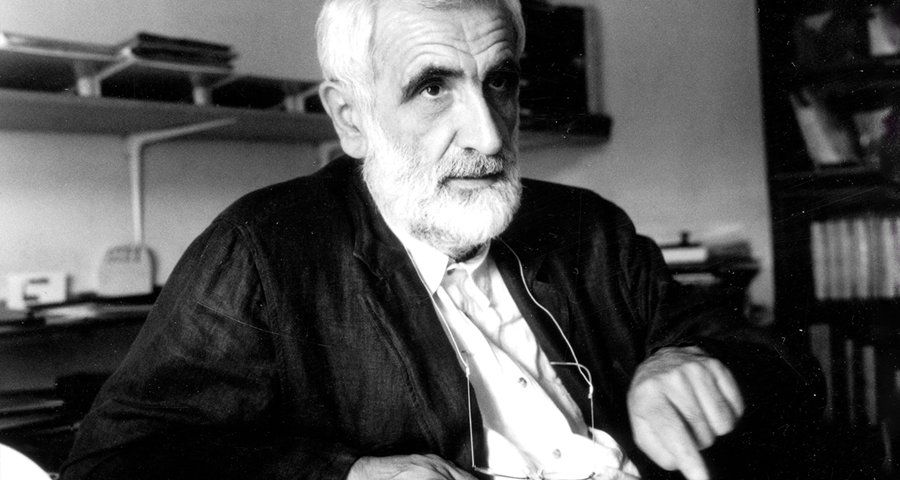

Enzo Mari (born April 27, 1932, in Novara, Italy–died October 19, 2020) was a noted Italian post-Modernist artist, writer, and product and furniture designer who incorporated ideas of the arts and crafts practices and of communism as an essential part of his design practice and philosophy opposing the idea that good design is a privilege for the wealthy.

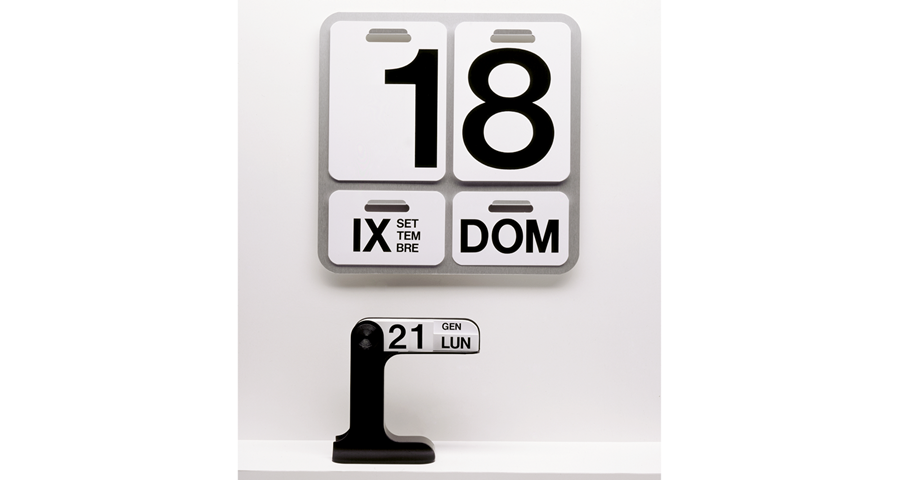

Affordability was a very important objective for Mari. He always aimed at creating design objects that were intuitive, elegant, functional, low cost and that would make a personal connection with their users. During his design process, Mari would become intimately involved with the artisans and manufacturers to ensure that his objectives of functionality, quality, and cost of his designs were met. In spite of his high standards, during his career Mari built strong collaboration with numerous design shops and furniture manufacturers of the time such as Artemide, Alessi, Zanotta, Driade, and Muji.

Of all of the numerous design projects along Mari’s career, Proposta per un’Autoprogettazione (Proposal for a Self-Design) occupies a special place due to its ability to deliver a message through the creation of an object. In 1974, he published the book Autoprogettazione with instructions on how to build easy-to-assemble/do-it-yourself furniture using as raw material only rough boards and nails. In the book, Enzo Mari uses the term Autoprogettazione as a concept to bring awareness of the process of “making” and design, and instructs the reader to build practical and useful furniture pieces through very simple techniques; hoping that the benefits drawn from this process of “making” would be more valuable than the object being made.

5 things to know about Enzo Mari:

1. Throughout his career, Enzo Mari created more than 2000 projects

Working almost incessantly for over 60 years, Mari was an intellectual, teacher, artist, exhibition-maker and much more. He always moved freely between disciplines, and saw no distinction between the type of projects he worked on – whether it be furniture, exhibition making, product design, graphic design or artistic installations. His depth of research and relentless rigour produced a body of work like no other – and leaves a legacy that extends far beyond the realm of design.

2. Mari studied fine art and stage design

In his early 20s, Mari enrolled at the Brera Academy of Fine Art, where he could be accepted without a high school diploma, as he had had to previously cut short his education in order to support his family. To begin with he studied painting and sculpture, but dropped out of this course as he was unsatisfied with the answers he received to his incessant questions. He finally enrolled in stage design, honing his technical drawing skills and developing his research into visual perception, experimenting with colour, volume, form and depth. Mari designed and won awards for his sets for operas by Puccini and Calderón de la Barca.

3. He made designs for children, and advocated for the importance of play

Mari thought play was not a form of amusement, but a way to understand the world. He famously said that the Nobel Prize should be awarded to two-year-olds, because he was fascinated by how quickly children learn about the world through a process of trial-and-error. As a young father in the 1950s, he noticed that many toys did not encourage creative thinking or autonomy in children, and observed how his own children’s enjoyment came from games that granted freedom in play. At first produced on a relatively small scale, Mari designed some of the most iconic children's puzzles and books that are still in production today.

4. For Mari, design was a means to transform society

Among his contemporaries, Mari was known as ‘design’s conscience’. His lifework was advocating for the social responsibility of design and designers, who for him ought to be at the service of society, not themselves. He also thought design should elevate the experience and status of the people producing objects, and not just serve those that bought them. In fact, many of his projects were experiments in de-alienating production line work, or in restoring autonomy and creativity in workers. For Mari, these were ways to practice equality, raise collective consciousness, and ultimately transform society to be more equitable.

5. He continues to be a role model for younger designers

Mari foresaw the ecological and societal dangers of our consumerist society and our throwaway culture. For him, the only real key to a sustainable future was producing less. At a time where surplus and inequality in distribution of goods is as acute as ever, Mari’s reflections on what good design is and should be, resounds far and wide. Generations of younger designers across continents - whether his former students or simply admirers - continue to reference his ethos, by challenging production processes, striving for essential and durable forms, or advocating for the importance of play. Mari’s donation of his archive to the city of Milan is also a gift to younger generations, whom he always believed in and whom he hoped would take learnings and inspiration from his work.

“We need to get rid of the idea of global profit, finance, industries and brands. We need to get rid of advertising, and of all forms of sponsored communications, of the world of forms with no essence that has replaced our kids’ school and education. Of all that exists to convince us that we need what we do not need, and that knowledge, wisdom and success can be easy and require no effort. We need to get rid of all the family-driven morals that could be all fine and well by themselves but that are all nonetheless blind. And we need to open our eyes towards a new collective ethic. And then, we may also have new designs. Because the first condition to create good design is passion for transformation.”

Enzo Mari